This is the Best Practices guide.

Tap on a topic and then subtopic below to navigate this guide.

This is the Best Practices guide.

Tap on a topic and then subtopic below to navigate this guide.

Motivational interviewing is a person-centered approach to counseling and rehabilitative services in which individuals are encouraged to identify their own goals and the discrepancies between the current situation and those goals, and to discover, with unconditional support, a way forward.

This strategy follows a non-judgmental style in which resistance to change is accepted as normal and natural, and the goal is to help the individual, weigh the consequences of choices and behavior in the context of his or her own desired outcomes.

The goal of motivational interviewing might be simply put as strengthening motivation for change.

The following are seven core principles of Motivational Interviewing:

Motivation to change is elicited from the client, and not imposed from without. Emphasis on coercion, persuasion, constructive confrontation and the use of external contingencies go against the spirit of motivational interviewing.

It is the client’s task, not the practitioner's, to articulate and resolve his or her ambivalence. They describe ambivalence as a conflict between two courses of action. The practitioner's task is to facilitate expression of both sides of the ambivalence impasse, and guide the client toward an acceptable resolution that leads to behavior change.

Direct persuasion is not an effective method for resolving ambivalence. While tempting to be helpful by offering persuasive arguments for change, practitioners usually create resistance to change in their clients.

The motivational interviewing style is generally a quiet and eliciting one. To a practitioner accustomed to confronting and giving advice, motivational interviewing can appear to be a hopelessly slow and passive process.

The practitioner is directive in helping the client to examine and resolve ambivalence. The operational assumption in motivational interviewing is that ambivalence or lack of resolve is the principal obstacle to be overcome in triggering change. Once that has been accomplished, there may or may not be a need for further intervention. Skills training, if needed, can focus on the skills the client has identified he or she needs to make the changes he or she has identified.

Readiness to change is not a client trait, but a fluctuating product of interpersonal interaction. Resistance and denial (lack of engagement, low engagement, no-shows and cancellations) are seen not as client traits, but as feedback regarding therapist behavior. Client resistance is often a signal that the practitioner is assuming greater readiness to change than is the case.

The therapeutic relationship is more like a partnership or companionship than expert/recipient roles. The practitioner respects the client’s right to make choices about behavior and consequences of the chosen behavior.

Competencies of motivational interviewing are a framework that details the delivery of motivational interviewing. Motivational interviewing competencies consist of six domains that act as guidelines for successful motivational interviewing.

Engaging with a person is the foundation of motivational interviewing. Maintain a person-centered style to understand a person's dilemma and values. Engaging also refers to the overall spirit of motivational intervieing. The overall spirit of motivatioanl interviewing highlights open mindedness in collaborating with a person, while recognizing his/her autonomy. This includes:

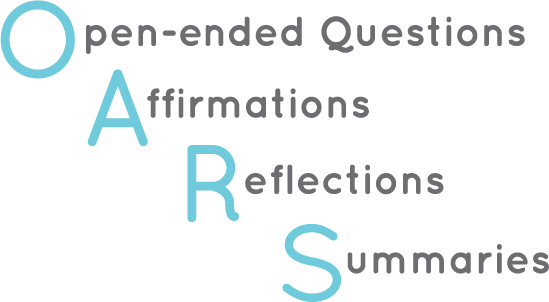

Practicing the spirit of motivational interviewing combined with active listening increases engagement with a person. Using microskills demonstrates active listening. Microskills are basic skills in a practitioners repertoire, but may be overlooked when focusing on larger interventions. The acronym OARS that describes the microskills. Microskills are referred to with the acronym OARS. OARS is an acronym for the core active listening skills that are essential to motivational interviewing. OARS stands for:

Open-ended questions are encouraged in motivational interviewing because they elicit the client's thoughts, feelings, preferences and goals. Open-ended questions are also person-centered because they do not lead toward a right or wrong, yes or no answer.

One easy strategy for asking open-ended questions is the first word. For example, think about how you would answer a question that starts with That starts with “Do you,” or “Are you.” Now think about how might answer a question that starts with “Why,” “How,” or “What.”

Affirmations acknowledge effort, willingness or ability, communicate positive regard, and emphasize a person's strengths and resources. They must be genuine, but can be a simple as “You've really given this a lot of thought” or “You worked really hard on that.”

Reflections are an effective strategy for demonstrating that you are listening, and for improving understanding. There are essentially two types of reflective responses, simple and complex.

Simple reflections essentially repeat back or paraphrase what a person has explicitly said. Complex reflections might explore the client's unspoken (implicit) meaning, feelings, intentions or experiences. Use the complex reflection strategy with care to avoid putting words in a person's mouth, or inserting your own opinions.

When bringing a conversation to a close you can put all four of the OARS strategies to work. Open-ended questions can engage a person further. "So what do you think we've accomplished today?"

Since an important objective in MI is to elicit change talk, skilled practitioners can use summaries to hone in on the change talk they have heard, and affirm it. "Thank you for efforts today. I know it was hard work. You've identified some very achievable goals."

Summary statements bring together key points and offer these back as a form of broad reflection on where the conversation has led. "What I hear you saying is that you're ready to make some changes in your..."

Recognizing are obstructions to active listening. Thomas Gordon identified 12 Roadblocks. These roadblocks interfere with a person's momentum toward change. There may be an apporpriate time to use some of these roadblocks, but it is important to avoid using these rodblocks during motivational interviewing. Thomas Gordon's 12 Roadblocks are as follows:

| Roadblock | Description | |

| 1 | Ordering, directing, or commanding | A direction is given with the forcfully or authoritatively. Authority can be actual or implied. |

| 2 | Warning or threatening | Similar to directing but implies consequnces, if not followed. This implication can be a threat or anticipation of a negative outcome. |

| 3 | Giving advice, making suggestions, providing solutions | The therapist uses expertise and experience to recommend a course of action. |

| 4 | Persuading with logic, arguing, lecturing | The practitioner believes that the person is not capable of reasoning through the problem and needs help in doing so. |

| 5 | Moralizing, preaching, telling clients their duty | The implicit message is that the person needs direction in appropriate morals. |

| 6 | Judging, criticizing, disagreeing, blaming | The common element among these four is an implication that there is something wrong with the person or with he/she said. This includes simple disagreement. |

| 7 | Agreeing, approving, praising | This message gives approval to what is being said. This cuts off the communication process and may imply a rough relationship between speaker and listener. |

| 8 | Shaming, ridiculing, name calling | The disapproval may be overt or covert. Generally, it's directed at fixing a problematic behavior or attitude. |

| 9 | Interpreting, analyzing | This is a very typical and tempting practice for couselors: to find the real problem or hidden meaning and give interpretation. |

| 10 | Reassuring, sympathizing, consoling | The purpose is to make the person feel better. Similar to approval, this is a roadblock that obstructs the spontaneous flow of communication. |

| 11 | Questioning, probing | Questions can be mistaken for good listening. The purpose is to explore further, to find out more. A hidden communication is the implication that a solution will be found when sufficient questions are asked. Questions can also obstruct the spontaneous flow of communication, leading the converstaion in the direction the questioner desires, but not neccesarily the speaker. |

| 12 | Withdrawing, distracting, humoring, changing the subject | These imply that what the person is saying is not important or should not be pursued. |

Focusing includes finding a focus in the conversation, agenda setting, and offering information and advice. Throughout the process of finding a focus, engage in a discussion about behavior change, while making it clear that it is the person's choice to make a change in behavior. Collaborate with the person to find a specific agenda for the conversation. Ensure a focus on the agenda throughout the conversation. Seek a person's permission prior to offering information or advice, and ask the persons prior knowledge and concerns before offering advice.

Evoking transitions the converstation to focus on motivational interviewing. Evoking encompasses selective eliciting, selective responding, and selective summaries. Examine disparities between a person's current behavior or situation and their goals, values, or self-perceptions. Listen for a person's change talk. Respond to a person's change talk with elaborating questions to highlight the person's motivation for change. Use OARS to elicit and reinforce change talk and a dedication to change. Respond to a person sustain talk in a respectful manner without reinforcing the sustain talk.

Planning change requires negotiating a change plan and commiting to the plan. Recognize flags that indicate a person may be ready to commit to generating change. Summarize the person's visualization of the issue, including reasons/need for change and ambivalence about change. Encourage a person's commitment talk by using evocative questions, and listen for his/her response. If a person is still ambivilent about change, revert back to OARS skills. Collaborate with a person using OARS skills to help him/her identify goals and establish a particular change plan. Once a change plan is identified, summarise this plan, and ask simple closed ended questions. If a person is not ready to commit to change, use OARS skills to revisit the issue and address any ambivalence.

Generic competencies are used throughout the process of motivational interviewing. These competencies incorprate demonstrating knowledge of and aptitude to work within professional and ethical guidelines, knowledge of basic motivational interviewing principles, and ability to explain rationale for using motivational interiviewing with a person.

Meta-competencies are the overarching keys to motivaitonal interviewing. It includes the use of relevant aspects of motivational interviewing knowledge and skills to plan and shape the intervention to the needs of individuals. Construct sessions and manage appropraite pacing. Choose and skillfully use appropriate motivational interviewing skills and strategies.

The best way to learn how to use motivational interviewing is by practicing motivational interviewing. The following video is an example of motivational interviewing in action.

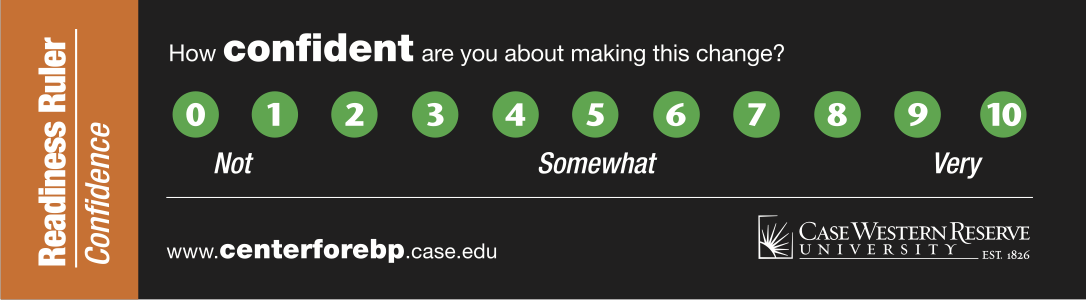

The readiness ruler is a resource to help you grasp where a person is in their path towards change. There are two rulers: the importance ruler and the confidence ruler. The importance ruler gages how important change is to a person at the present time. The confidence ruler reflects how confident a person is in commiting to change at the present time. Upon determinging a person's comfort with change using the readiness rulers, probe for reasons for his/her answer. The follow up questions are a crucial part of the process, as they provide more incite into a person's readiness for change. A question, such as "Why 5 and not 6?" can help a person think more about what it would take to make small, manageable steps toward change.

Source: Case Western University

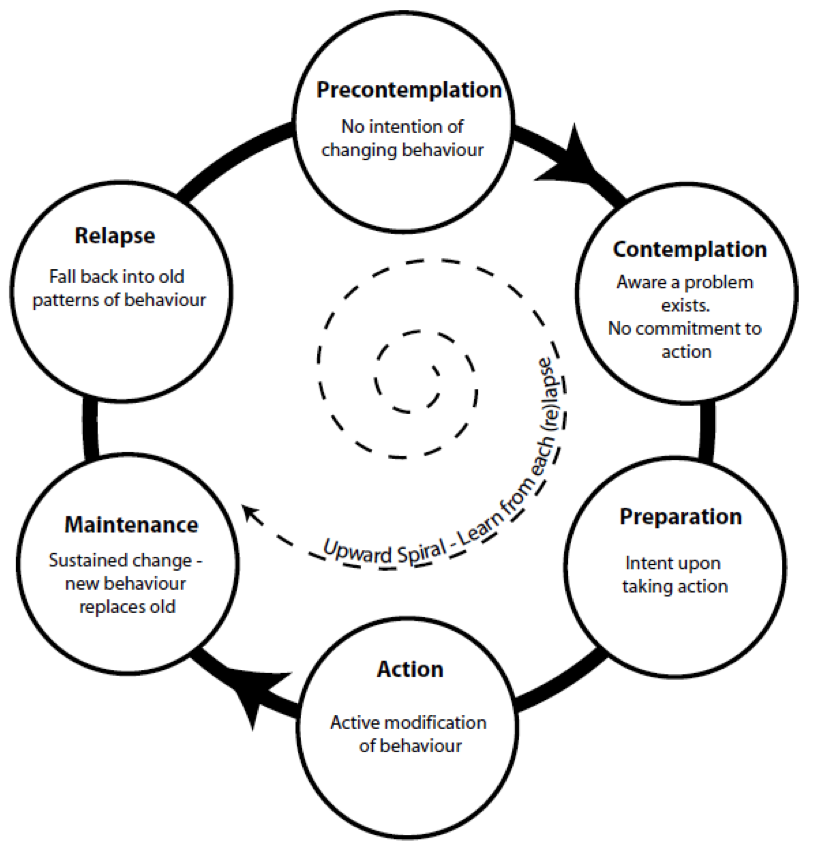

The Wheel of Change reflects the cycle a person experiences when undertaking change. For each step a person encounters on the Wheel of Change, there is a corresponding practitioner response.

| Stage | Description of Stage | Practitioner's Response |

| Precontemplation | Not yet considering change, unwilling, or unable to change | Establish rapport, ask permission, and build trust. Raise doubts or concerns with the person about current, unwanted behavior patterns. Express concern and keep the door open. |

| Contemplation | Aware of the problem and seriously considering change, but no commitment to take action | Raise awareness of the needed change by observing behavior. Help resolve ambivalence about change. Address the person's belief that change is possible. |

| Preparation | Leaning towards change. Intends to change and makes small behavioral changes. | Encourage these steps and support the change process. Commit to making change a top priority. Consider possible barrier and how to lower them. |

| Action | Takes steps to change but has not yet reached stabalization. | Make an action plan, reinforce changes, and provide support guidance. |

| Maintenance | Maintaining the accomplishment of change, and practicing a daily routine and appear to be sustaining the change. | Support continued change and help with relapse prevention. Review the person's coping strategies. Review the person's long-term goals. |

| Relapse | Starting the unwanted behavior again. | Assist the person in re-entering and understanding the change cycle. Support positive decision to get back on track. |

This guide is a living document. We want to improve it with your help. Do you have questions? Found a typo? Find yourself wanting more information? Please send us your thoughts about anything in this chapter by tapping on the link below.